Making Space for Artists in the World of Finance

By Sarah Elisabeth Sawyer (Choctaw Nation), Artist in Business Leadership Fellow 2015

Making space for artists in conversations about Native Community Development Financial Institutions (CDFI) and capacity building for communities nationwide, First Peoples Fund was excited to take part in the 4th Annual Native CDFI Capital Access Convening. Tosa Two Heart (Oglala Lakota), First Peoples Fund Program Manager of Community Development, presented reports and models from our Indigenous Arts Ecology program at the convening as part of a panel of presenters that included Vicky Holt Takamine (Native Hawaiian), Duncan Ka’ohu Seto (Native Hawaiian), and Liz Takamori (Native Hawaiian).

Facilitated by First Nations Oweesta Corporation, a longtime First Peoples Fund (FPF) partner, the Native CDFI Capital Access Convening brought together stakeholders who share a commitment to the financial and cultural well-being of Indian Country. As a convening specifically for Native institutions, attendees were able to find shared experiences, brainstorm solutions relevant to their communities and build meaningful networks with one another. The First Peoples Fund panel was able to pull-in the importance of recognizing the presence and importance of art in Indigenous communities in a way that was relevant to the future of Native CDFIs.

“Art and culture are so ingrained with everything we’re doing and what Native CDFIs are doing, but to recognize it is essential,” Tosa says. “I’m hoping our presentation inspired that with the CDFIs. I’m so thankful to Oweesta for giving us that space and opportunity to share.”

After Tosa finished her part in the session — “Investing in Indigenous Arts Ecology” — she turned the platform over to a panel featuring individuals from the PAʻI Foundation. The foundation has a deep shared history with First Peoples Fund and is currently a 2019-2020 Indigenous Arts Ecology (IAE) grantee.

Duncan Kaʻohu Seto (Native Hawaiian), a master artist and a certified FPF Native Artist Professional Development (NAPD) trainer, brought his artist perspective to the discussion.

“We used the metaphor of weaving,” Kaʻohu says. “First Peoples Fund was one strand of fiber, PAʻI another, and then myself, and we are all intertwined.”

PAʻI Executive Director Victoria (Vicky) Holt Takamine (Native Hawaiian) emphasized how artists are activists and change-makers, as well as preservationists. She connects artists with CDFIs, helping both parties understand how their work benefits the local community. Often, artists do not realize how a small loan can propel their business forward.

“I don’t think that our community really engages with our CDFI here in Hawaii for the kind of support they need to continue their practice,” Vicky says. “That’s one of the things we need to do in reaching out to artists and cultural practitioners.”

On the flip side, Native CDFIs are often unaware of the critical role artists play in the economy. Artists are at the forefront of perpetuating Native traditions and lifeways, yet they are overlooked regarding how much of their work is essential to sustaining their communities.

“CDFIs need to figure out how they can work with the artists a little closer,” Vicky says, “and how they can support the artists or really, the activists, in helping to protect our natural and cultural resources that are so vital to our survival.”

As shown in our 2013 market study ( Establishing a Creative Economy: Art as an Economic Engine in Native Communities ), artists need access to six resources to succeed and continue practicing their art. Native CDFIs are a massive component in this, meeting some of those needs for art markets, capacity building, capital, credit, and access to supplies in creative ways. Those investments drive change and make a sustainable difference in Indian Country.

“I presented our data highlights regarding the Indigenous Arts Ecology report and talked about how it would benefit Native CDFIs to invest in artists,” Tosa says. “It’s important to invest in relationships with the artists.”

“We’re so different, arts and finances, it’s unusual to have an artist who is well rounded in both,” Kaʻohu says. “Besides creating artwork, to be able to see the financial part of it. CDFIs can help artists get help if we need more materials, if a photographer needs a new camera. If you could just get a loan from a CDFI, it can help you out with canvas, paint, new chisels, things like that.”

Several FPF Indigenous Arts Ecology grantees also attended the convening, including Four Bands Community Fund, Native American Community Development Corporation, and Lakota Funds. These Native CDFIs have long recognized the value of reaching out to Native artists. They work to get artists bankable, offer business training, and create new markets for them to showcase their work. Over the years, these Native CDFIs have invested resources, time, and energy in developing artists in their communities.

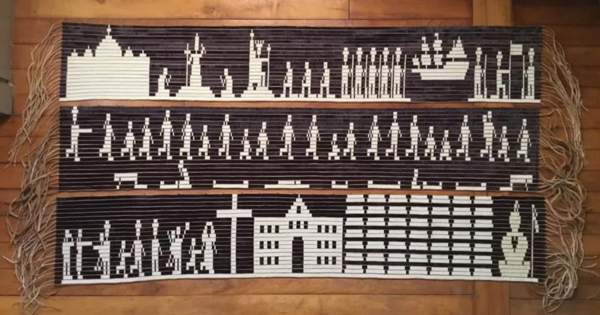

Amidst the financial sessions at the convening was a time to engage in traditional Native Hawaiian weaving with weavers from Nā Mea Hawai’i, a community-centered organization. CDFI participants gathered to weave a “memory mat” and continue discussions.

“There’s a saying in Hawai’i that you can hear, but you can still work with your hands,” Kaʻohu says.

In a unique way, having those weavers take part in the financial convening summed up the conversation we wanted to bring. In the world of small loans and credit lines, artists should be recognized as a source of economics and community wealth building.

“We’ve always invited our CDFI to provide training for our financial literacy classes,” Vicky says. “That was twofold — doing financial literacy training, but also provide an opportunity to introduce the CDFI and their services to our artists. We are trying to encourage the CDFIs to get their message out, and to share how they can be supportive of the work that the artists are doing.”