Restoring What Was Lost: Julia Marden’s Creative Journey

2025 Community Spirit Awardee Julia Marden (Wampanoag Tribe of Gay Head) reflects on the pull between reality and fantasy, history’s beauty and brutality, and her unstoppable will to create.

From an early age, she knew she wanted to be an artist, experimenting with anything she could find. That search for the right fit ended with traditional arts. “Once I started, there was no question left,” she says. Now, she creates seven days a week: “There’s nothing I’d rather do.”

“Once I started, there was no question left,” she says. Now, she creates seven days a week: “There’s nothing I’d rather do.”

In her twenties, Julia worked at a Wampanoag homesite, where a training project introduced her to twining. She picked it up instantly—what she calls “genetic imprinting.” Within two weeks she had finished her first bag, started another, and was soon teaching the craft.

As a child, she was told art might not work out. She understands the push for security, but chose her own path: “Thankfully, I was strong enough to follow it.”

“Always listen to your gut,” she says. “Our ancestors are always with us, communicating. If you’re open, they’ll never steer you wrong.” For Julia, acceptance guides everything: she wouldn’t change a thing.

“Our ancestors are always with us, communicating. If you’re open, they’ll never steer you wrong.” For Julia, acceptance guides everything: she wouldn’t change a thing.

And yet, both humbled and honored to receive the Jennifer Easton Award, Julia admits she’s having a hard time accepting this as reality.

It began with a photo shoot with Matika Wilbur. Next, she received the Princess Red Wing Award and now the Community Spirit Award. Julia hedges. There’s more. “Did you know? I’m also a statue. I was also made into a statue.”

Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts commissioned Mohawk sculptor Alan Michelson to create two statues for its front steps. Across from Micmac artist André Strongheart stands Julia Marden, Wampanoag knowledge-keeper. Spotting it on her way to park, she laughed: “It’s platinum! I could not dream this up in my real life.”

She credits the recognition to her turkey feather cape—the first made in 400 years. Known for her masterful twined basketry, storage bags, and Eastern Woodland traditions from painting with a toothpick to regalia and dolls, Julia calls the mantle “pretty much the height of twining.”

In fact, the loom built for the project was 7’ tall (6’+ across). She spent two months sorting thousands of feathers, just to get started.

Julia’s new relationship with the MFA Boston promises an upcoming exhibit including a full woman’s outfit she is making, and the turkey feather mantle.

Julia has restored three traditions to her nation: the mantle, overlay embroidery, and horseshoe crab bags. “Bringing back things that were lost is extremely important. The ancestors want to see them return.”

“Bringing back things that were lost is extremely important. The ancestors want to see them return.”

Her achievements belong to her people—her grandmothers, who said to watch over her as she works; her three granddaughters, who are now third-generation weavers; and the little girl who fought to become an artist.

Most recently, she joined fellow tribal member Paula Peters in reviving wampum belt-making, inspired by viewing the British Museum’s collection during a London layover.

Over 100 tribal members participated in making the belt, including making the beads. Julia had never made a 5-foot, 21-row belt. To familiarize herself, she knocked one out. Hired to create designs, Julia’s initiative resulted in her becoming the project’s weaving manager.

The project’s purpose was education, in part because Wampanoag people hope against hope that Metacom’s lost belt remains intact, perhaps unrecognized, to be returned one day. Today, Wampanoags don’t have a single ancient belt.

Meanwhile, Julia has gone a bit, belts.

“One of the purposes of the wampum belt is to document our history. It’s basically our written language.” The English adopted the practice of trading wampum with inland peoples. “That’s why, “ Julia says, “there’s a myth that wampum equates to money.” Traditionally, wampum is used in ceremonials, burials, gifts, and treaties and mainly to document.

“One of the purposes of the wampum belt is to document our history. It’s basically our written language....That’s why, “ Julia says, “there’s a myth that wampum equates to money.”

“Our storytellers were the keepers of our wampum belts, and they would travel from community to community during the winter months, telling our stories over and over. I’m doing that now.”

Since her work travels from exhibits rather than villages, Julia creates images for broad audiences, knowing she may only reach a few amid generations of indoctrination. “Don’t take my word for anything,” she urges. “Check into it—keep your eyes open.”

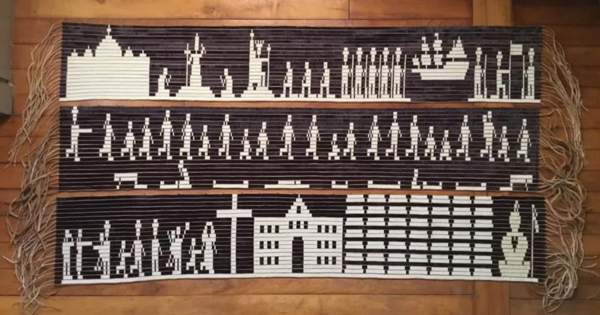

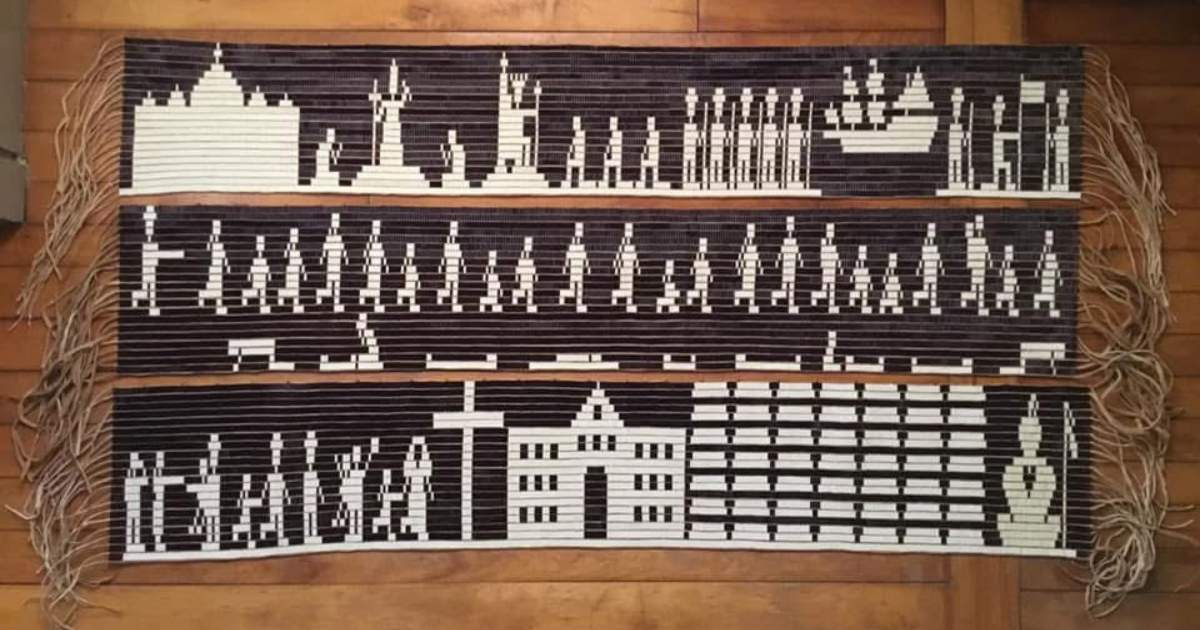

Her series A Telling of the Wampanoag Story spans creation, harmonious seasonal life, first contact, plague graves, the bloodiest war per capita on American soil, slavery, and finally today’s powwows: “we’re dancing, celebrating, doing our thing.”

Another series, Architects of Genocide, moves from the Doctrine of Discovery to the Indian Removal Act, to Kill the Indian, Save the Man.

First Encounter Beach is a belt. Another belt follows the dream of a dear friend, a repatriation officer. He wears the belt now during the ceremony, repatriating his ancestors.

When Julia was invited to speak about her belts at Aquinnah, she wasn’t prepared for the experience of sharing the belts’ intense themes with an audience. She creates her work in privacy. She handles whatever comes up in seclusion. Presenting the work in public, “it went from bad to worse, to worse.” By the time she reached the Repatriation Belt, Julia was sobbing. “I just hadn’t really thought it through.”

“I might not be able to accomplish everything on my list, but it’s my goal.” Even while talking, she conceives of a new idea for a belt. “I’m driven. That’s why I devote so much time.”

“I might not be able to accomplish everything on my list, but it’s my goal.” Even while talking, she conceives of a new idea for a belt. “I’m driven. That’s why I devote so much time.”

Julia says, “The funny thing is…” If not for a debilitating injury, she likely would have stayed in the workforce. She says when she was working—and it checks—“I worked overtime all the time…50-60 hours a week. And then I got struck down. I was nearly bedridden. I wouldn’t have had time to do all this… Everything I’ve done, I’ve done since I was injured.”

“You’ve got to keep going forward and make it a positive.”